Blood Will Tell

The murder of Mickey Bryan, a quiet fourth-grade teacher, stunned her small Texas town. Then her husband, a beloved high school principal, was charged with killing her.

Did he do it, or had there been a terrible mistake?

Part I

by Pamela Colloff

May 23, 2018

I.

Most mornings, the sky was still black when Mickey Bryan made the short drive from her house on Avenue O, through the small central Texas town of Clifton, to the elementary school. Sometimes her car was the only one on the road. The low-slung, red-brick school building sat just south of the junction of State Highway 6 and Farm to Market Road 219 — a crossroads that, until recent years, featured the town’s sole traffic light. Mickey was always the first teacher to arrive, usually settling in at her desk by 7 a.m. A slight, soft-spoken woman with short auburn hair and a pale complexion, she prized the solitude of those early mornings, before her fellow teachers appeared and the faraway sound of children’s voices signaled, suddenly and all at once, that the day had begun.

Click to read Part 1 of 2

One morning, Mickey did not show up for work. It was a Tuesday in the fall — Oct. 15, 1985 — and the air was damp from a heavy rainstorm that rolled through town the previous night. Mickey’s classroom was dark when a fifth-grade teacher, Susan Kleine, walked by at 7:15 a.m. She stopped, puzzled, and looked inside; she tried the door, but it was locked. At first, she figured her fanatically punctual friend was running off photocopies on the other side of the building, but by 8 a.m., there was still no sign of her, and Kleine hurried to Principal Rex Daniels’s office. “Did you forget to call a sub?” she asked him, bewildered. “Mickey’s not here.”

Daniels asked his secretary to call the Bryan home, but no one answered. He knew Mickey’s husband, Joe, the longtime principal of Clifton High School, was out of town at a conference, so he directed his secretary to phone Mickey’s parents, Otis and Vera Blue. They did not know where their daughter might be — they last saw her the previous afternoon when she stopped by their home on Avenue L — but they promised to go check on her right away. “I felt something was wrong,” Daniels later wrote in a statement for the police, “and left school to go to Mickey’s house.”

Clifton lies 100 miles southwest of Dallas, on an empty stretch of prairie land gouged by creeks and river valleys. The town was, and remains to this day, populated by some 3,000 people, many of them descendants of the Norwegian farmers who settled in southern Bosque County before the Civil War. Both Bryans were familiar and beloved figures around town. Mickey, who was 44, once held the title of Miss Clifton High School, an honor bestowed on her by her classmates, though she shied from attention. She was guarded even around the few people she allowed to get close, while Joe, who was a year her senior, thrived on human connection. Warm and expressive, with a gift for putting people at ease, he had an open, friendly face and blue eyes that were always animated behind his large wire-rimmed glasses. At the high school, he was an ebullient presence, an educator with such enthusiasm for his job that at Friday-night football games, he seemed to be everywhere at once, calling out to students and their extended families without stumbling over a name.

Mickey and Joe had known each other since elementary school. They first crossed paths when Joe, who grew up on a farm about 40 miles southeast of Clifton, on the outskirts of Waco, visited a cousin in nearby Mosheim, where the Blues then lived. They did not begin dating until more than two decades later, in 1968, when they were earning master’s degrees in education: she at Baylor University in Waco, he at Trinity University in San Antonio. Joe was getting over the dissolution of a four-year marriage that had never taken root, and in Mickey, he found a centering force. Mickey was quiet, unflappable and fiercely practical — a woman who, despite the norms of Texas beauty, eschewed makeup and favored flats. She was charmed by Joe’s demonstrativeness, and when he told a story about her or publicly praised her, as he often did, she patted his arm with bashful affection. They wed in 1969 in a private ceremony in the home of Joe’s childhood pastor. Mickey did not want the fuss of a church wedding.

The Bryans shared a common sense of purpose; they believed in the transformative power of teaching, and when they moved to Clifton in 1975 after Joe was offered the job of principal, they immersed themselves deeply in the lives of their students. If families’ budgets fell short, Joe and Mickey stepped in, quietly paying for hot lunches, senior trips, new clothes. Together they devoted part of each summer to devising lesson plans for Mickey’s incoming fourth-graders and brainstorming new ways to reach her most reluctant learners. In the evenings, Joe often sat beside Mickey and helped her grade papers. They were different from other married couples, a number of women who knew them noted appreciatively; Mickey and Joe seemed more like a team. They both loved being around children but were never able to have their own — an immutable fact of their marriage that seemed to only draw them closer. Nearly every evening, they went on long walks around Clifton, where it was common to see them strolling hand in hand down the town’s wide residential streets, absorbed in conversation.

Daniels was the first to arrive at the Bryans’ single-story brick house, which overlooked a well-tended yard on the southernmost edge of town. The garage’s double doors were up, and Mickey’s brown Oldsmobile was parked inside. The day’s Waco Tribune-Herald and Dallas Morning News lay in the driveway. Daniels rang the doorbell. The house was dark and quiet.

Moments later, the Blues hurried up the walkway with a spare key, and Daniels followed them in. Vera led the way, calling out her daughter’s name. She was the first to reach the master bedroom, and when she stepped inside, Daniels heard her cry out. He and Otis followed close behind her. In the bedroom, blood was everywhere — spattered across the bed, the ceiling, all four walls. Daniels immediately took hold of Vera and instructed her and Otis to go to the living room. He did not step any farther into the bedroom, but as he stood in the doorway, he could tell that Mickey was dead.

Her body lay across the length of the unmade bed, her outstretched legs dangling over the mattress’s edge. Her pink nightgown was drawn up to the top of her thighs, and she was naked from the waist down.

Daniels rushed to the phone in the kitchen and called the police. “It looks like someone broke in and shot Mickey,” he said.

The house where Mickey and Joe Bryan lived in Clifton, Texas when Mickey was murdered in 1985. (Dan Winters for The New York Times)

Word of the killing traveled quickly around Clifton that morning. “We were all dumbfounded,” Cindy Horn, who worked as a teacher’s aide at the elementary school, told me. “We couldn’t wrap our minds around it. How could anyone hurt Mickey?” Amid the collective anguish and shock that everyone felt, she said, “our first thoughts were about Joe — that Joe was going to be completely devastated.”

One hundred and twenty miles away, at the Texas Association of Secondary School Principals’ annual conference in Austin, Joe was taken aside by the organization’s executive director, Harold Massey, not long after 10 a.m. The two men had known each other for years, and as they huddled in the foyer of one of the Hyatt Regency’s conference rooms, Massey got right to the point, telling Joe what little he knew: Mickey had been shot to death in their home. “Are you sure you have the correct information?” Joe stammered. “Mickey Bryan of Clifton, Texas?” Massey helped him to a chair as he grew unsteady on his feet.

Three principals whose help Massey enlisted found Joe near the check-in desk. He appeared unmoored, his face gone slack with shock. He sat by himself, holding his head in his hands. They took him upstairs to his hotel room, where he lay down in bed, shivering. Still dressed in his suit and tie, he pulled the covers over himself.

Two longtime colleagues of his from Clifton — Richard Liardon, the school superintendent, and Glen Nix, the assistant elementary school principal — arrived around noon to take him home, and when Joe saw them, he broke down. Before he slid into the superintendent’s car, Joe handed the keys to his black Mercury to one of the principals who had come to his aid; he agreed to ferry it back to the Waco area. “Very little was said,” Nix told me of the more-than-two-hour drive from the state capital to the green, rolling hills of Bosque County. “Joe sat in the back with his head down and cried the whole way.”

II.

The Bryan home was cordoned off with yellow crime-scene tape when the three men pulled up outside shortly before 3 p.m. Law-enforcement officers had swarmed the house; the Texas Rangers, who often aid the state’s rural police departments with homicide investigations, were working the scene, as were Clifton police officers, sheriff’s deputies and technicians from the state crime lab. Dazed, Joe fielded investigators’ questions from the superintendent’s car. Of primary interest to them was whether the Bryans had any firearms in the house, and Joe explained that he had a .357 pistol in the bedroom, which he kept loaded with birdshot to dispatch the rattlesnakes and copperheads that sometimes roved the yard. The conversation was brief, and after investigators returned to their work, Joe was driven to the Blues’ house, where friends and neighbors had gathered to pay their respects. “What am I going to do without Mickey?” he asked Susan Kleine again and again. When she embraced him, he held on to her as if he might fall without her support.

Investigators would remain at the house until after midnight, poring over the crime scene. They had little to go on; the neighbors had not seen or heard anything unusual, and there were no leads to chase down — no bloody fingerprints that might have narrowed the search for the killer, no shoe-print impressions to try to match. (No semen was detected on vaginal swabs that were later collected for the rape kit.) Yet slowly, a picture of the crime began to emerge. Mickey had been shot four times: once in the abdomen and three times in the head. A blast to the left side of her face had been fired at extremely close range. A search of the house revealed that the .357 was missing, as was Mickey’s gold wedding band, her watch and a diamond-studded ring. Tiny lead pellets, which lay scattered around the bedroom, were also embedded in her wounds, leading investigators to surmise that she was killed with the .357. The house displayed no obvious signs of forced entry, but a Texas Ranger who found the back door locked was unable to conclude whether it had been secured before, or after, officers arrived. A cigarette butt was discovered on the kitchen floor, though neither of the Bryans smoked. Taken together, the evidence seemed to point in one direction: Mickey had been the victim of a burglary-turned-homicide.

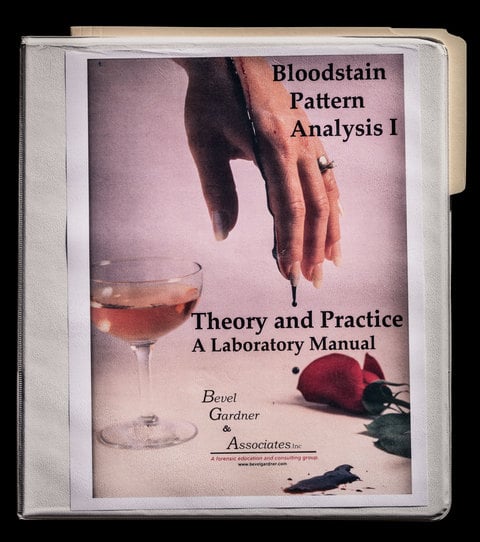

Hoping to glean new insights, the Texas Rangers called in Robert Thorman, a detective with the Harker Heights Police Department in nearby Bell County, who arrived that evening. Thorman was trained in a forensic discipline called “bloodstain-pattern analysis,” whose practitioners regard the drops, spatters and trails of blood at a crime scene as treasure troves of information that contain previously unseen clues and can even illuminate the precise choreography of the crime itself. Thorman peered through his magnifying glass, moving it in slow, sweeping motions. Mickey’s body had been removed by then — only the baby blue mattress, which was sodden with blood, remained — but he surveyed the reddish-brown flecks that dappled the walls, studying their contours and dimensions. He tacked strings to five small bloodstains on the wall above the headboard, extending each strand down to the mattress below. But his work, in the end, yielded little new information, just a theory that Mickey’s killer had most likely been standing on the west side of the bed when he or she fired the gun.

As the investigators went about their work, Joe spent the night with his mother, Thelma, in Elm Mott, the small town north of Waco where she lived. She had moved there after Joe and his siblings — his older brother, James, and his twin brother, Jerry — left home and had remained after their father’s death. Joe lay awake, his mind racing, until exhaustion overtook him.

At the funeral home in Clifton the following day, he learned that Joe Wilie, the Texas Ranger who was helming the investigation, wanted to speak with him, and he headed over to the police station. A career lawman who had spent 15 years as a highway patrolman before being promoted to the state’s premier law-enforcement division, Wilie cultivated an air of unassailability, his face impassive under the brim of his white Western hat. He carried himself with the assurance of someone who could get to the bottom of the mystery that lay before him. Joe did not take a lawyer with him, nor did the direction of the investigation suggest he should. Despite Wilie’s brusque, no-nonsense style, the interview was not an adversarial one.

As Wilie led him through a series of routine questions about Mickey, their marriage and the days leading up to the murder, Joe explained that nothing seemed out of the ordinary the last time he spoke with his wife. He told Wilie that he called her from his hotel room around 9 p.m. on Monday, Oct. 14, the night before her absence from school. He had been watching the Country Music Awards, and she had been averaging grades. She was in good spirits, he added, and they talked about the rain.

The Texas Ranger listened as Joe talked but shared few details about the investigation, mentioning only that they had found the metal box in which Joe told them the previous day he and Mickey kept $1,000 in cash. But there was no money in it, and the box was covered in dust, suggesting that no one had recently disturbed it. Wilie advised him to look around the house to see if he might have placed the money elsewhere. Joe had no theories to offer about the crime, and the interview did not produce any new leads. “Mr. Bryan indicated to writer that he would have no idea who would want to kill his wife,” Wilie noted in his report.

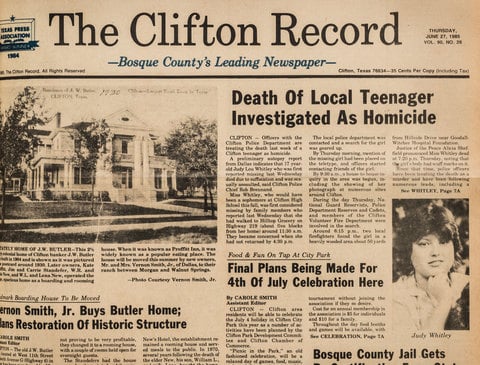

Wilie and the other investigators working on the case needed more, and fast. This was the second unsolved murder that year in a town where people routinely left their doors unlocked and no one could easily recall the last homicide. Just four months earlier, on June 19, Wilie was called to Clifton to investigate the killing of a 17-year-old named Judy Whitley. Her nude body was discovered in a dense cedar thicket on the western side of town. The details of the crime scene shocked Clifton residents; ligature marks scarred the teenager’s wrists, indicating that she had been bound, and gray duct tape covered her mouth. The medical examiner would later determine that she was sexually assaulted and died of suffocation. Wilie assisted with the Whitley case, which was still no closer to being solved.

When Mickey was killed, less than a mile away, it sent another jolt of panic through the community. The inability of law enforcement to make a single arrest only stoked residents’ fear and uncertainty about whether the crimes were random acts of violence or somehow linked. Susan Kleine, the teacher whose classroom was across the hall from Mickey’s and who lived alone, began spending the night at her sister’s house, where she always slept with a gun within reach.

Though Wilie and the other investigators working on the Bryan case were under enormous pressure to make an arrest, they struggled to develop any new information. In the days after Mickey was killed, the Texas Department of Public Safety flew a helicopter over a pasture near the Bryan home, looking for clothing that might have been discarded by a transient who was reported to have been in the area. Rangers questioned members of a concrete crew who were working on a house on Avenue O and examined the shoes and pants of a yard man who was believed to have been in the vicinity of the Bryan home on the morning Mickey was found. They interviewed the family of a teenage girl who saw a peeping Tom at her bedroom window a few nights earlier. It wasn’t much.

Then, on Saturday, Oct. 19, four days after the murder, Wilie got his first break when he learned that Charlie Blue, Mickey’s older brother, had some important information. Blue, who lived in Plant City, Florida, where he served as the vice president of an agrochemical company, had managed to catch a flight to Texas that Tuesday after learning of his sister’s death. The siblings were not especially close. Blue’s forceful personality had always stood in stark contrast to his sister’s soft-spokenness, and though there was no animosity between them, they had not spoken since he came to visit in February, eight months before her death. Joe was not particularly close with his brother-in-law either, but the two men had a cordial relationship; Joe had helped out from time to time around the farm in Clifton that Blue owned, and together they built fences, vaccinated cattle and mended water lines.

As Blue would recount in a sworn affidavit he wrote the following week, it was that Friday, with no apparent progress in the case, that he decided to call Bud Saunders, an ex-FBI-agent-turned-private-investigator who was on retainer with his agrochemical company. “I asked Bud Saunders if he could come to Clifton and do some checking as there were some things that were bothering me about my sister’s death,” Blue explained in his affidavit. Blue did not tell Joe that he was bringing a private investigator to town or share with his brother-in-law what was troubling him.

Saunders wasted no time; he made the 300-mile trip from the West Texas city of Midland, where he lived, arriving at the Dairy Queen in Clifton the next afternoon. “I went into the Dairy Queen and suggested to Bud that we leave and ride around so I could discuss my concerns,” Blue wrote. “We drove around the countryside for a while talking about the murder.”

The two men were in Joe’s car, which Blue borrowed the day after Mickey was found dead. He’d asked Joe if he could use it for the duration of his stay, and Joe, who was being driven between Elm Mott and Clifton by family members, had been glad to oblige. At some point during the drive, according to Blue, he pulled over so that he and Saunders could relieve themselves, and Saunders ended up getting mud on his boots. Looking for something to clean them with, Blue opened the trunk; immediately, he spotted a cardboard box with a flashlight inside it whose lens was facing up. “I noticed that there were what appeared to me to be blood specks on the lens,” Blue wrote. He handed the flashlight to Saunders, who agreed that the tiny, dark flecks looked like blood.

Blue and Saunders drove back into town with the flashlight stowed in the trunk and headed toward the Bryan home. “I knew that a cleanup and painting crew had been working on the house and thought that some of the officers might be there,” Blue wrote. Finding the house unattended and the front door unlocked, Blue and Saunders decided to let themselves in. Discovering no one there, they left, drove to a pay phone and called the Texas Rangers.

Any number of details in their story, which Saunders told over the phone and later recounted at the Ranger station in Waco, should have spurred Wilie to dig deeper. Why did the men not drive straight to the Clifton Police Department with their discovery? Why did they enter the Bryan home by themselves, and what did they do inside? Why did they not call law enforcement from the Bryans’ phone?

But if Wilie pushed them to explain more, there is no record of it. Instead, he executed a search warrant on the Mercury shortly after midnight. The trunk was inspected and photographed, as was the car’s clean interior, which showed no trace of the mud that dirtied Saunders’s boots. (Saunders later said he cleaned the mud off with his pocketknife.) The flashlight — its lens stippled with reddish-brown specks, each roughly the size of the tip of a pencil point — was taken to the state crime lab for further examination.

Wilie did not impound the Mercury; instead, he released it to Blue once the search was complete, and Blue and Saunders returned to Clifton, leaving the Mercury in the driveway of the Bryan home around 4 a.m. Three hours later, Blue was gone. He headed to Austin, where he boarded a flight later that morning bound for Tampa.

Nobody told Joe any of this. Everything that transpired during Saunders’s visit — the discovery of the flashlight, the entry into Joe’s home, the examination of his car by law enforcement — was unknown to him when he picked up his keys at Mickey’s parents’ house that Sunday. At that point, the car had been out of Joe’s possession for four days.

The following morning, he called Chief Rob Brennand of the Clifton Police Department to report a surprising discovery. On his way back to Elm Mott, Joe told Brennand, he stopped to get gas. After opening the trunk to grab a fuel additive, he said, he spotted a brown money bag, which contained $850, that belonged to him. He then remembered putting it there two weeks earlier, when he and Mickey had driven to Waco to go shopping. In the mental fog he had been in since the murder, he had forgotten that he had taken the cash out of the metal box in the bedroom.

Wilie’s search of the trunk had not turned up the money bag, however; when he heard Joe’s story, he was certain that Joe was lying. He became even more suspicious when the results from the crime lab came back: The specks on the flashlight lens were human blood, type O — the same blood type as Mickey’s, but not Joe’s. Blood typing was the most precise tool that law enforcement had for such evidence before the advent of DNA testing, though it was hardly definitive; nearly half the population has type O blood. Whose blood it was could not be settled with any certainty, but from that point on, the investigation hurtled forward under the assumption that it could have come only from Mickey. A crime-lab chemist also found a few tiny plastic particles on the flashlight lens that, she said, appeared to have the same characteristics as fragments of the birdshot shells that were found at the crime scene. Wilie felt confident enough in the evidence to believe that he had his man.

On Wednesday, Oct. 23, 1985, eight days after Mickey was found dead, Wilie, Brennand and the Bosque County sheriff appeared at the doorway of Thelma Bryan’s home in Elm Mott. It was evening by then, and the men had arrived unannounced. Joe looked at them expectantly, assuming that they had come to tell him of an important break in the case. Instead, Wilie informed Joe that he was under arrest for his wife’s murder. “Are you serious?” Joe said. He looked in disbelief at the three men who were standing in his mother’s den. “On what evidence?” he demanded. He was not given an answer before he was put in handcuffs and led outside, where a Waco TV news crew — who had been tipped off to the arrest — was waiting.

III.

Clifton, Texas. (Dan Winters for The New York Times)

In Clifton, and among the farther-flung group of young people who attended Clifton High School during the decade that Joe served as principal, the news of his arrest was greeted with incredulity. “I remember feeling there had been a terrible mistake,” said Kelly Carpenter-Daniels, who was a senior at what is now the University of North Texas when she learned that Joe had been charged with Mickey’s murder. Joe had guided her through various high school crises and disappointments, dispensing both encouragement and tough love when needed, while always, she told me, assuring her of her intelligence and worth. “He took a profound interest in all of our lives,” she said. “He was able to reach teenagers in a way that few adults could. There was a deep bond there, like there would be with a great coach. He was beloved.”

Carpenter-Daniels’s most indelible memory of Joe dates back to a day when she and a classmate decided to cut school and drive to Lake Whitney, the area’s primary tourist attraction and a popular destination for anyone who dared to skip class. She and her friend were splashing around in the water when something caught her eye; she glanced up and saw Joe standing on the bluff above them in his suit, hands on hips, frowning down at them. “The disappointment on his face is something I’ll never forget,” she told me. “He didn’t raise his voice or say he was going to call our parents. He sat us down and told us that we were the leaders of the school, and that leaders are supposed to lead.” The fact that he bothered to make the 25-mile trip each way to ensure that she went to class and did not allow her grades to slip left a lasting impression. “He was an instinctively caring and compassionate person,” she said. “I couldn’t imagine him hurting anyone, much less murdering his wife.”

Her feelings were shared by many of Joe’s colleagues, who took it as an article of faith that he was innocent. “I didn’t have any employees at that time who felt he was capable of what he was accused of,” said Richard Liardon, the school superintendent at the time. Joe was seen as lacking both the motive and the temperament to have committed such a brutal act; this was a man they knew well, and he had always been slow to anger. “He was calm and easygoing; I never once saw him lose his temper,” Johnny Paul Holmes, a special-education teacher, told me. “Sometimes during the last period of the day, he would to go to the choir room and just sit and play the piano. That was Joe.” Making the charges seem all the more improbable was the widely held perception that the Bryans’ marriage had been a harmonious one and that Joe had been a loyal and attentive husband. “He was Mickey’s champion and her protector,” said Cindy Horn, the teacher’s aide. “I would have hated to have been the person who crossed Mickey and had to deal with Joe.”

Many of the Bryans’ friends and co-workers were interviewed in the weeks after Joe’s arrest and subsequent indictment. One of them was Kleine, the fifth-grade teacher who first noted Mickey’s absence and whom Wilie had brought in for questioning. As one of Mickey’s few close friends, Kleine (who now goes by her married name, Ellis) had seen the Bryans’ relationship up close. “I knew Joe could never have hurt Mickey,” Kleine told me. “He adored her. There was no scenario in which Joe killing Mickey made any sense to me.” At the police station, she was floored by Wilie’s very first question, which left her troubled about both the direction and the soundness of the investigation. “He began by asking me if I thought Joe was effeminate,” she explained. “He said there were rumors that Joe was gay, and he asked me what I knew about that.” Kleine pushed back but was unnerved when Wilie persisted with this line of questioning. She was aware of just how incendiary such an accusation could be for a high school principal in a deeply religious, socially conservative town. “We’re talking about someone’s life here,” she implored the Ranger.

What, precisely, set in motion the inquisition into Joe’s sexuality is unclear, but it may have been something that Wilie discovered in the trunk of Joe’s Mercury: a Chippendales pinup calendar. Joe would later insist that it was a gag gift he and Mickey bought for a single friend of theirs. But investigators seized on the idea that Joe was gay, repeatedly probing the subject in interviews with his friends and colleagues.

Suddenly, the very qualities that had endeared Joe to his community — his demonstrativeness, his warmth, his volubility — were cast in a different light. “Homo tendencies?” one investigator jotted down during an interview. Similar observations were scrawled in notebooks and on scraps of paper that litter the case file: “He gay?” “Feminine acting.” “Absolutely no homosexual advances but Joe is a ‘toucher’ when talking to people.” “Joe would bake pies & cook etc rather than fish, play poker.” One theory that investigators entertained was that Joe killed Mickey because she had discovered his dark secret.

The known facts suggested nothing so unusual. Joe’s phone records, which investigators obtained, revealed an ingloriously conventional existence; in the month before the murder, he had called Mickey, his mother, his older brother, a first cousin, a vitamin shop, a contact-lens store and a hospital. Nevertheless, investigators pursued the narrative that he had a secret gay life, and though no such rumors existed before the investigation, unfounded stories began to percolate of a supposed relationship with a male student and forays to New Orleans gay bars. So fevered did the speculation become that Brennand, the police chief, visited Linda Liardon, the ex-wife of Richard Liardon, at her real estate office to ask about the “nature” of Joe’s relationship with the superintendent. This was an insinuation that Linda, who was recently divorced from Richard, found laughable. “I told him, ‘Just because Joe plays the piano and drinks Dr Pepper instead of beer doesn’t make him gay,’” she said. She informed the police chief that she thought he could use his time more judiciously, given that in her estimation he had not one unsolved murder on his hands, but two.

As every facet of his public and private life was held up to scrutiny, Joe, who was free on a $50,000 bond, kept a low profile, electing to remain in Elm Mott, 40 miles away. He was put on paid leave after his arrest, and for the first time since his career as an educator had begun, his hours were no longer set to the familiar rhythm of the school day. His life narrowed to his mother’s house and his defense team’s office in Waco, where he and his attorneys, Charles McDonald and Lynn Malone, met to prepare for his trial. He seemed less concerned about the prospect of being found guilty, Linda Liardon told me, than eager to move on. “He just wanted the whole thing cleared up,” she said. “His attitude was, ‘Let’s get this behind us so we can go look for who killed Mickey.’” Though many of his friends and colleagues pledged to testify on his behalf, Joe was always aware, when he drove into Clifton once a week to check on the house and mow the lawn, that he was suddenly, and perhaps irrevocably, dispossessed. With the exception of his next-door neighbors, who always greeted him warmly, people often kept their distance.

Most painful to Joe was the rupture of his relationship with the Blues. Charlie filed a lawsuit to tie up Mickey’s estate so Joe could not draw from her savings to pay for his defense, and Otis and Vera, lost in grief, cut off communication. According to Joe, his pastor called that fall to relay the message that several members of First Baptist did not feel comfortable with him in attendance and suggested that he hold off on coming to church until his case had been decided by the courts. Faith had always been the organizing principle of Joe’s life, and the rejection left him adrift at a time when he needed spiritual support most. His sense of abandonment was compounded when Richard Liardon made the trip to Elm Mott in early 1986 to ask on behalf of the school board if Joe would tender his resignation. “We don’t know how long this is going to drag on,” the superintendent told him. Anguished at the idea of surrendering his job, Joe protested, giving in only after Liardon persuaded him that doing so would be in his students’ best interests.

By then, the weight of his community’s collective doubts was bearing down on him. In the course of just a few months, Joe had been stripped of everything: his career, his spiritual fellowship, his reputation and the person he loved most. He frequently visited her, driving out to the small white chapel near the farming community where Mickey grew up. In the cemetery there, he would stop at the granite marker that was etched with her name. What tormented him as he sat beside her grave was not the rejection of the people he loved, or even the loss of “the oneness” that he said he and Mickey had shared, but his conviction that he had failed her. “I would go and talk to her,” he told me. “I felt guilty because I didn’t protect her. I’d always been — the whole 16 years of our marriage — her security blanket, for lack of another word, and in spite of everything I tried to do, I couldn’t save her.”

Clifton Elementary School, where Mickey Bryan taught fourth grade. (Dan Winters for The New York Times)

IV.

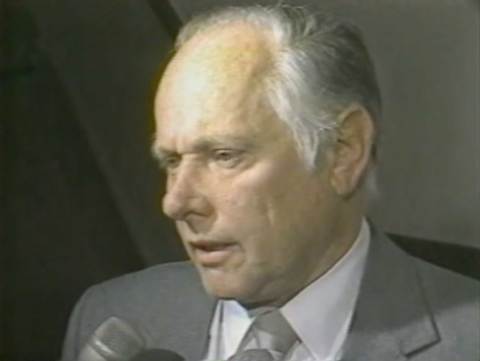

In March 1986, when the State of Texas v. Joe D. Bryan commenced in the century-old limestone courthouse in Meridian, the county seat, the courtroom’s wooden benches were crowded with spectators, many of whom had made the short drive from Clifton to observe both the trial and the man at its center. To virtually everyone in attendance, it was a shock to first behold Joe — former Sunday school teacher, Rotarian, high school principal to a generation of Clifton’s residents — seated somberly at the defense table. His standing in the community was such that many of the potential jurors who appeared for jury duty reported knowing Joe in some way or having heard about the case. His attorneys, who were pleased that their well-regarded client was no stranger to a Bosque County jury pool, had not requested a change of venue. “This is his home,” Charles McDonald told TV news reporters outside the courtroom in his melodious twang. “He desires, elects and wants to be — if he has to be — tried by people that know him best.”

There was good reason for the defense to feel confident at the start of the eight-day trial. It was entirely unclear at the outset if the state’s case was winnable. Prosecutors had decided to try Joe “prematurely … without thoroughly investigating the case,” McDonald opined, adding that his opposing counsel “had a lot of exhibits but very little evidence.” District Attorney Andy McMullen’s tepid opening statement did little to dispel such skepticism. He did not lay out a narrative or commit to a theory of the case, nor did he express the sort of fervent moral outrage that can be effective in glossing over a scarcity of facts.

But what McMullen lacked in pugilistic style was made up for by his co-counsel, a bare-knuckled adversary named Garry Lewellen, who served as special prosecutor. Though it is not uncommon for a DA lacking big-city resources to seek assistance on a challenging case, Lewellen had not been retained by Bosque County but by Mickey’s brother, Charlie Blue, who was paying his legal bills. (The law differs from state to state, but generally, a victim’s family may hire a special prosecutor so long as the DA maintains control of the case.)

Blue’s presence loomed large from the very beginning, because he had discovered the flashlight. With no eyewitnesses who could place Joe in Clifton at the time of the murder, no motive and no forensic evidence that conclusively tied him to the crime scene, the prosecution’s case rested almost entirely on this one piece of evidence. Investigators told the jury that they had located one of Joe’s fingerprints on the back side of the reflector and another on the battery inside. Joe, in fact, had never denied the flashlight was his; he typically kept it in the bedroom, he said, and last remembered seeing it there. What was unclear was what relevance it had to the murder. Was Joe being truthful when he said he did not know how it had gotten in the trunk? Was the blood on it Mickey’s? Was the flashlight connected to the crime, and if so, how?

The state expended surprisingly little energy trying to answer these questions during the first days of the trial. The most direct testimony came from Wilie, when he told the jury that investigators had observed bits of plastic at the crime scene, which they believed to be fragments of shell casings, and that he had seen two such fragments on the flashlight lens itself. A crime-lab chemist, Patricia Almanza, appeared to support his claim when she testified that she had examined a fragment from the lens under a microscope and that it had “similar properties to what was found at the scene.”

Whether her findings were conclusive or not was never scrutinized; Joe’s lawyers did not press for a detailed description of her testing protocols or ask what other materials might share “similar properties.” They failed to point out to jurors that the plastic bits were not easily discernible in photographs of the flashlight, and they did not question how the fragments had managed to stay on the lens for nearly a week — during which time the flashlight was picked up, handled and transported in the back of a moving vehicle.

Charles McDonald, Joe Bryan’s defense attorney.

Other forensic evidence either pointed away from Joe or proved to be more bewildering than clarifying. Two human hairs found in the cardboard box in the trunk did not match either of the Bryans, nor did 13 latent prints lifted from the master bedroom and bathroom, though the possibility existed that the prints predated the murder, because they had not been left behind in blood. The significance of the most intriguing clue — an unidentified palm print on the headboard of the bed, which did not match Joe’s — would never be determined; the inked impressions of Mickey’s palms that were taken at the time of her autopsy were performed incorrectly and, as a result, could not be used for comparison. The prosecution would try to assign sinister motives to the fact that Joe had kept a pair of plastic gloves in his trunk, gloves on which Almanza said she detected a “very minute” amount of blood. But the gloves — the clear, disposable type that were dispensed at gas-station pumps — looked clean and unworn, and there was not enough blood to yield even a blood type.

Arguably the single most consequential piece of evidence was the cigarette butt on the kitchen floor. It was this clue, more than any other, that threatened to undermine the prosecution’s case by suggesting the presence of a stranger in the Bryan home. Yet early on in the trial, Wilie asserted that he had brought it into the house himself. “It stuck to the bottom of my boot outside, and I tracked it into the floor,” he told the jury. When McDonald asked him on cross-examination how he knew he had done so, Wilie replied, “Well, you’ll have a witness that will testify to that, I was told.” That witness was a Clifton police officer named Kenneth Fields, who claimed he had seen the cigarette butt fall from Wilie’s boot, though he admitted he never wrote down what happened. Similarly, Wilie made no note of it in his 25-page report. The prosecution went on to argue that Justice of the Peace Alvin James had tossed the cigarette butt to the ground outside the Bryan home; the blood group substance detected on the cigarette indicated that it had been handled by someone with type A blood — which James, along with about one-third of the population, had.

To win a conviction, however, prosecutors needed to do something much more complicated than deflect attention from details like the cigarette butt. They had to explain how Joe, who was attending the principals’ conference in Austin, could have been in Clifton at the time of the murder. Their account was constrained by two indisputable facts. Joe’s last call with Mickey, which was placed from his hotel in Austin, ended at 9:15 p.m. on Oct. 14. He was also seen the next morning — when she was found dead — by witnesses at the conference in Austin.

The prosecution’s case, then, required the jury to believe the following: Shortly after speaking with Mickey, Joe slipped out of the Hyatt and drove 120 miles to Clifton, at night, through heavy rain, even though he had an eye condition that made night driving difficult; shot his wife, with whom he had no history of conflict; ditched the pistol and jewelry yet kept a flashlight speckled with blood in his trunk; drove 120 miles back to Austin; and re-entered the Hyatt and stole upstairs to his hotel room — all in time to clean up and attend the conference’s morning session, and all without leaving behind a single eyewitness.

This was a difficult story to prove, and some of the state’s own witnesses lent credence to the defense’s case. James Smith, the principal to whom Joe had given control of his car when his colleagues came to drive him back to Clifton, testified that Joe showed no hesitancy in turning over the keys to the Mercury — not the expected behavior of someone presumed to have fled a messy crime scene hours earlier in the same vehicle. Its interior, Smith added, was scrupulously clean.

When Charlie Blue took the stand on the fourth day of the trial, the prosecution sought to cast him as a sympathetic figure — an older brother who had, by investigating the case himself and hiring a special prosecutor, gone the extra mile to find justice for his sister. The trim, self-assured 47-year-old told the jury he initially harbored no suspicions of his brother-in-law. He decided to call a private investigator, he explained, only after the local funeral home director suggested he do so. “An insurance company had called to verify her death, about paying an insurance claim,” Blue said. “Whether that triggered him to suggest to me that I should get an investigator, or whether he thought that it might not be handled thoroughly, I don’t know.” Blue told the jury that he soon called Saunders, and he recounted how he and his private investigator had driven around the countryside the following day and made their startling discovery. “When I opened the trunk of the car,” he said, “I saw this flashlight that had red specks on it, or dark specks, and my immediate reaction was, ‘That looks like blood.’ ”

When McDonald rose to cross-examine Blue, he sharply questioned the witness, seeking to expose the fragility of the state’s case, which hung almost entirely on Blue’s credibility. “Have you ever thought about it — perhaps you have, Mr. Blue — how would you prove to this jury that you didn’t put that flashlight in that box?” McDonald asked.

“I’m here to testify what I found,” Blue said.

“I’m asking you, sir, if you were called on — other than your word and perhaps the word of Mr. Saunders — how can you tell us and prove positively that you didn’t put it in there?”

“I didn’t,” Blue shot back. “I found it in there.”

The defense’s fiercest attack on Blue came when Wilie was on the stand and McDonald pressed him to provide a rationale for the state’s case against Joe. “You haven’t come up with one motive at all, have you, for this man to kill this woman?” he said.

“She’s worth over $300,000 to him dead, if you want to surmise a motive,” Wilie countered, referring to Mickey’s life insurance and savings.

McDonald turned this detail back on Wilie. “You know that Mr. Blue has filed a suit claiming some of this money up in Cleburne, Texas, claiming all of it, don’t you? You know that’s pending, don’t you?”

“I know he’s filed a suit, yes, sir.”

“You know he’s got some other lawyers up there. If this man’s convicted, Mr. Blue stands to gain some money, don’t you?”

“I didn’t know who stood to gain the money,” Wilie said.

“Haven’t checked that out?”

“No, sir.”

During Wilie’s time on the stand, he worked diligently to refocus the jury’s attention. He testified that a pair of Joe’s discarded underwear, which was stained with semen that matched Joe’s blood type, was “moist” when investigators found it in the wastebasket of the master bathroom — implying that Joe had been in the home not long before Mickey’s body was found. Wilie conceded that he had made no mention of the stain’s wetness in his report, though he insisted that the underwear “tended to stick together.” Almanza, the crime-lab chemist, was unable to substantiate that they had been moist. Still, the word “moist” became prosecutors’ favorite rhetorical flourish as they called jurors’ attention, again and again, to the semen stain. They made references to the Chippendales calendar with equal enthusiasm, darkly suggesting that Joe was not the upright citizen he claimed to be. “It’s evidence of a kind of perverted behavior,” McMullen told the jury. The state’s innuendo-laced language was a powerful tool at a time when AIDS was a relatively new and little-understood public-health threat, and in a place where, under state law, gay sex was still considered a criminal act.

Prosecutors’ insinuations also provoked a broader question: If Joe was concealing the very nature of who he was, what else was he hiding? In the absence of any solid evidence that placed him in Clifton at the time of the murder, they shifted their focus to discrediting Joe himself. McMullen called a Hyatt employee to the stand who had an odd story to tell. He testified that Joe had returned to the hotel, after he was arrested and was out on bail, claiming that a security guard had approached him during the principals’ conference and asked for temporary access to his hotel room, keys and valuables so that the hotel might try to catch a housekeeper who was stealing from guests. According to the Hyatt employee, Joe explained that he had agreed to help the guard but that he had come to wonder about the incident after his wife was found dead. No one who fit the guard’s description worked at the hotel, nor was there any evidence of such a sting operation, and prosecutors, who treated the story with derision, suggested that Joe had concocted it in an effort to divert attention from himself.

That was all anyone was ever able to dig up on Joe. The state never produced any witnesses who spoke of a troubled marriage or a violent past; they never located anyone who had caught a glimpse of him in Clifton in the late evening of Oct. 14, 1985, or the predawn hours of the following morning. As the state’s case limped to a close, jurors were left with only a mishmash of evidence — the flashlight, the underwear, the cigarette butt — but no clearer picture of how, or why, Joe would have killed the woman he loved.

How We Reported This Story

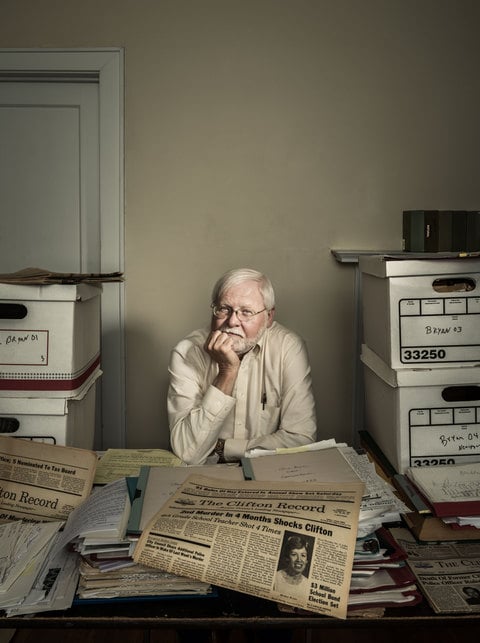

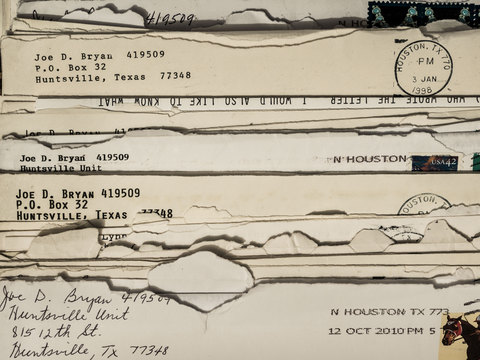

This story provides a detailed and intimate look at a 33-year-old murder case. To reconstruct the case for this narrative, Pamela Colloff drew on voluminous court records, more than 4,000 pages of trial testimony dating back to the 1980s, current litigation over DNA analysis and the ongoing writ of habeas corpus proceeding. She also had access to the extensive investigative notes compiled during the murder investigations of Mickey Bryan and Judy Whitley — including Texas Ranger records, Clifton Police Department reports, and investigators’ handwritten notes. Though several central players in the case declined to participate, Colloff reviewed affidavits they had written, sworn testimony, and legal briefs to portray these individuals’ viewpoints. She also drew upon decades of correspondence between W. Leon Smith, the former editor in chief of the Clifton Record, and Joe Bryan. Finally, Colloff conducted interviews with dozens of past and present residents of Clifton, whose memories and insights were invaluable.

V.

When Robert Thorman settled into the witness box on the fifth and final day of the state’s case, it marked a turn in the prosecution’s fortunes. Thorman was the bloodstain-pattern analyst who was called to the Bryan home when investigators were still working the scene. As an interpreter of bloodstains, Thorman possessed a singular expertise, and the prosecution would use this to bring its hazy narrative into focus, lending a sense of scientific certainty to an otherwise equivocal set of facts.

Forensic scientists and criminalists had long looked at bloodstains at crime scenes as potentially valuable clues. A few even attempted to trace the trajectories of the blood back to its source and, in doing so, to reverse-engineer the crimes themselves. They believed that bloodstain-pattern analysis — the examination of the shape, dimension, location and distribution of bloodstains — could help them answer critical questions. What type of weapon caused the fatal wounds? Where was the victim standing when he was shot, stabbed or bludgeoned to death? Was she killed at the location where she was found, or was her body moved there? Trying to find the answers to these questions required an understanding of fluid dynamics and high-level math. But in the decade leading up to Joe’s trial, bloodstain analysis began to migrate out of research labs and into police departments. Thorman was one of a growing number of officers who were taking weeklong training in the discipline and who sometimes testified as expert witnesses. Though these police officers lacked the advanced scientific education of their predecessors, they, too, began to use bloodstain-pattern analysis to reconstruct crimes. Blood, they held, had a story to tell.

The district attorney began by leading Thorman through a recitation of his credentials. The detective explained that he had served as a military police officer for 20 years before working his way up through the ranks of several small law-enforcement agencies and that he had been trained in bloodstain interpretation. The jury did not know that Thorman’s training was limited to a 40-hour class he took four months before Mickey was killed.

Thorman said that he arrived at the Bryan home after Mickey’s body was removed and that he carefully inspected the master bedroom, where he recalled there was “a vast amount of splattering.” He told the jury that the killer, too, must have had “a vast amount” of blood on him. But Thorman did not spend much time describing his analysis of the bedroom, because it had turned up little new information. At McMullen’s direction, Thorman focused instead on the flashlight.

The bedroom where Mickey Bryan was killed.

To win their case, the prosecution needed to tie the flashlight, which was found days after the murder, outside the Bryan home, to the crime scene. Thorman, under McMullen’s questioning, did exactly that. Photos of the flashlight that were shown to the jury revealed an object almost wholly devoid of blood, save for a scattering of tiny flecks on the lens and the occasional, minuscule speck on the side. To the untrained eye, it did not look like much, but Thorman claimed that the particular pattern on the lens had deep significance for the case. He identified the pattern as “blowback or, as commonly known, back spatter” — that is, blood that had traveled backward, at a high velocity, from a target. It was the unmistakable signature of a shooting, and of a shooting that had taken place at close range, as Mickey’s had. Back spatter “usually travels no further than 46 inches,” Thorman told the jury — an assertion that echoed earlier testimony from a forensic pathologist, who found that the greatest distance between Mickey and her killer at the time of the shooting was likely no more than a couple of feet.

Thorman’s testimony effectively erased any doubt about whether the flashlight was relevant to the case; he had, in essence, placed it in the Bryans’ bedroom at the time that the murder took place. Moreover, he told jurors, the lack of spatter on the flashlight’s handle indicated that someone had been holding it when it was sprayed with blood. “The handle portion indicates the flashlight was in the hand,” he said. By his telling, then, it had been both present at the crime and held by the killer.

During his time on the stand, Thorman made another critical finding that shored up the state’s case. Until then, prosecutors had not been able to provide an answer for the most troublesome question it faced: If Joe had killed Mickey and then fled with the flashlight, why was no blood found on the interior of the Mercury? Thorman himself had testified that the killer was covered in blood, yet Joe’s car was spotless. It was an inconsistency that called the state’s entire case into question, but once again, under McMullen’s questioning, Thorman offered an explanation. Blood was not found in other areas of the house, he told the jury, leading him to conclude that “the individual that committed or perpetrated the crime cleaned up prior to leaving that bedroom.” The killer, he added, had most likely done so in the bathroom — an assertion that did not appear to be grounded in bloodstain analysis; no blood was found in the bathroom other than some small drops on a receipt of the Bryans’ in the wastebasket. Still, Thorman theorized that the killer had wiped himself off there with a rag, changed his clothes and even slipped on a different pair of shoes before exiting the house.

McMullen took this idea one step further, asking a question that went far beyond the bounds of what a bloodstain-pattern analyst is qualified to evaluate. “There would have to have been shoes there to fit the killer then, would there?” the prosecutor asked, in an obvious allusion to Joe.

“I would assume that,” Thorman said.

McMullen rested his case later that afternoon. When it was finally Joe’s turn to speak, on the trial’s sixth day, he told of his devastation over his wife’s death and of the affection and respect that he and Mickey had shared. “We never gave each other any reason, nor any doubt, about our feeling and our love for each other,” he said. He insisted he never left his hotel room after he spoke with Mickey on the evening of Oct. 14 and recalled attending an 8:30 a.m. session at the principals’ conference the following morning. He also told the jury of his peculiar encounter with the hotel guard, a story that Lewellen, the special prosecutor, used as a cudgel in a blistering cross-examination that cast Joe as a fabulist. “I don’t know,” Joe repeated again and again, sometimes through tears, as Lewellen pressed him about different details of the case and hounded him to say who else could have killed Mickey. “I don’t understand any of this, never have from the very beginning,” Joe said.

No fewer than 36 defense witnesses followed — a succession of friends and former colleagues who each took the stand to praise Joe’s character and reinforce the notion that he could never have committed such a heinous act. But in the end, none of it mattered. Thorman’s testimony had made the state’s tenuous theory of the crime seem plausible, allowing the prosecution to gloss over the deficiencies of its case. Even McMullen seemed to acknowledge these weaknesses in his closing argument. “It was essential to have a special prosecutor in this case because as you’ve seen, that man” — he said, referring to Joe — “is shrewd. He’s intelligent, and it would take a great deal of effort to be able to prosecute him and prove his guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.”

In his thundering summation, Lewellen drew from Thorman’s testimony as he sketched a chilling portrait of the man sitting at the defense table. “Mickey didn’t go to bed and leave that house unlocked that night,” Lewellen declared. “She locked her door, and a man came in with a key, and after all hell broke loose in that bedroom, he cleaned up, changed clothes, wiped up that lavatory, threw [his clothes] in the bag, walked out that front door.” Then Joe, Lewellen added, “went right back, walking in the front door of the Hyatt hotel, whistling Dixie.”

Less than four hours after jurors began their deliberations, Joe rose from his seat and listened as the judge read aloud the verdict: “We, the jury, find the defendant, Joe D. Bryan, guilty of murder.” His punishment was later set at 99 years. At different times during the trial, Joe told me, he had wanted to scream at the top of his lungs — “to yell at everyone that I did not kill Mickey, and how could anyone think I could, or would, do such a thing.” But in that moment, as he stood in a state of disbelief, he was rendered mute.

VI.

In the summer of 1988, two years after Joe’s conviction, a longtime Clifton resident named Carole Smith was shopping at the Richland Mall in Waco when she spotted a man who looked just like Joe Bryan. He had the same wire-rimmed glasses, the same wavy brown hair, the same ruddy complexion — but he seemed to lack Joe’s sense of purposefulness as he meandered through the mall, gazing absently at the window displays. Smith, then an editor at The Clifton Record, the town’s weekly newspaper, knew Joe well — he had guided and reassured her many times when her son was navigating high school — and as the man came closer, she felt certain it was him. “Joe?” she called out.

That February, Joe’s conviction was overturned on a technicality, and though Smith knew that Joe had been released from prison, she had been unaware, until that moment, of his whereabouts. The ruling did not exonerate Joe; it only found fault with his trial. A three-judge panel had concluded that the trial judge erred when he denied a particular defense request to reopen testimony late in the trial. In doing so, the judge prevented Joe’s attorneys from reading to the jury a deposition they conducted with the Bryans’ insurance agent, in which the agent refuted a brief, but noteworthy, piece of testimony: Wilie’s claim that Mickey, upon her death, was “worth over $300,000” to Joe. (Her life insurance, it turned out, was valued at about half as much.) The ruling made no determination as to Joe’s guilt or innocence. He still stood charged with murder, and the Bosque County DA’s office would retry him the following summer. For the time being, though, Joe was a free man — or as free as a man can be while waiting to stand trial for a murder he had already been convicted of once.

Joe was glad to catch sight of Smith, his expression softening. “Carole,” he said, brightening. Smith asked him if he would like to sit and visit, and they settled on a nearby bench. She was mindful not to overwhelm him with questions. She listened, letting him guide the conversation. As he spoke, it was apparent that the strain of the trial and his incarceration had been almost more than he could bear and that he felt the need, even as shoppers strolled by them, to unburden himself. The words came quickly as he enumerated all that he had lost — “my wife, my job, my home, everything,” he said, his voice welling with disbelief, as if he were still trying to grasp how he had found himself in such a fantastical situation. It had been nearly three years since Mickey’s death, but he still had not had time to properly grieve, he told her. He said nothing about his time in prison, and Smith did not venture to ask him about it. When they rose to say goodbye, she embraced him and wished him well. “I got the feeling he didn’t have anywhere to go or anyone to talk to,” she told me.

By then, opinion in Clifton had turned against him, so much so that just talking to Joe at the mall could be seen as a radical act. The Record, which covered Joe’s first trial exhaustively, did not question the verdict; the reporter who was dispatched to write about it walked away believing that Joe was guilty. The prevailing wisdom held that the jury rendered its decision after hearing all the facts. “Most people felt he was probably guilty, because he’d been convicted, even if no one was real sure why he’d done it,” Richard Liardon, the former superintendent, told me. Many of Joe’s former colleagues and friends had distanced themselves from him since the trial, though privately, some still struggled to reconcile the man they knew with the person the prosecution had portrayed him to be. “It was very hard for me to believe Joe had taken Mickey’s life,” Cindy Horn, the former teacher’s aide, told me. Yet like most people in Clifton, she held the criminal-justice system in high regard. The widely held assumption was that law enforcement and the courts always got it right. “I based what I thought on the verdict,” Horn said. “I assumed Joe was guilty because he was found guilty.”

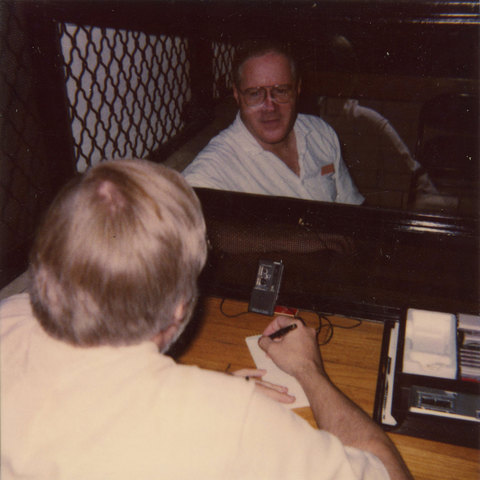

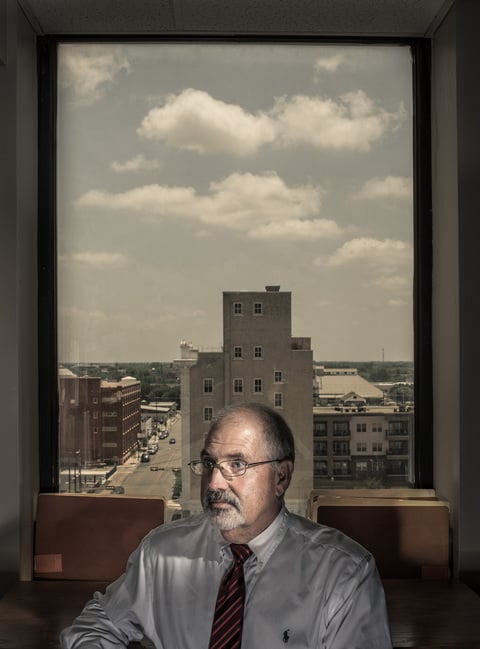

Joe Bryan at the Texas State Penitentiary at Huntsville, also known as the Walls Unit. (Dan Winters for The New York Times)

At his retrial, which spanned seven days in June 1989, the erosion in trust was visible: Joe’s witnesses had dwindled from 36 at the first trial to just five. Gone were the TV reporters, the crush of spectators and the sense that Joe, by virtue of his good reputation, could overcome a vigorous prosecution. McMullen, the district attorney, was again assisted by Lewellen, the special prosecutor, as they summoned largely the same witnesses who appeared at the first trial.

It was in every way a repeat of the story the prosecution told before. Wilie recounted the horror of the crime scene (“There was blood all over the bed. … Blood splattered on the ceiling, the walls”), and Blue narrated the moment he discovered the flashlight (“When I opened the trunk, there was a cardboard box, and my eyes just zoomed in on it”). McMullen asked Almanza, the crime-lab chemist, if a bit of blue plastic on the flashlight lens had the same “chemical properties” as shell casings at the crime scene, and she agreed that it did. And once again, when Thorman took the stand, he was the one who tied the disparate strands of the state’s case together.

Thorman told the jury not only that the flashlight was in the bedroom at the time of the shooting but also that the killer, before fleeing the scene, had changed into clothes that were already in the Bryan home. He delivered his findings with the authority of an expert, stripping away the ambiguities of the state’s case. As he spoke to the jury, he grounded his findings in the certainty of science. “Based on my knowledge and experience in bloodstain interpretation,” he said, “the flashlight itself was right next to or near the source of energy, that being the gun.” By the time the guilty verdict came down on the last day of the trial, it seemed like a foregone conclusion. Joe was again sentenced to 99 years.

Joe was sent back to the same prison where he was previously held: Texas’ oldest penitentiary, known as the Walls Unit in Huntsville, where the state’s execution chamber is housed. In letters back home to his mother, his older brother and the few friends who remained in touch with him, Joe was circumspect, revealing little about his existence behind bars or the emotional toll of incarceration. By then, he no longer heard from many people he loved — including Jerry, his twin brother, who distanced himself after Joe’s first trial. Even his last remaining Clifton friends gradually faded away. Linda Liardon wrote to Joe every now and then, but eventually she let the correspondence languish. “I was busy raising my boys, and life moved on,” she said. “I’m ashamed to admit that. But after a while, I struggled with what to say.”

Still, she was left with an uneasy feeling. After Joe’s first conviction, she told me, people had stopped talking about Judy Whitley’s death. “One rumor went around that maybe Joe killed her too,” she said. “I think wrapping all this violence up in one neat little package was comforting to people. Everyone could put this behind them and not have to think that maybe someone was out there who had gotten away with murder.”