Not funny. RIP to those involved. Horrendous story.

post also reported.

RIP to all that died in this terrible tradgedy.

Just bacuse you follow GAA dosent mean this should be taken down , show a bit of decency Horsebox you disgusting bigot.

i saw that Kev allright, RIP

this whole thread stinks

A slurry pit? Sounds like a right shit hole.

Dungeon.

V v poor taste all round.

I wouldn’t know what a slurry pit tastes like pal. How the hell do you know?

:lol:

There are two other threads on this topic.

I think this will just continue into an argument about whether the thread should be allowed or not and I’ve no interest to row in on that argument again.

So I’ll close this thread but I won’t be deleting it. As others have said earlier it’s not particularly tasteful or even funny (sorry Sidney) but not every thread on here is in good taste or is wildly funny. I will delete posts that are racist, or pose a legal threat or are blatant attempts to spam the site. And if anyone is personally offended by topics because of family background etc then by all means report them and I’ll help if I can.

As Sidney did point earlier we do have an unwritten rule on this site that if you can poke fun at one death you can poke fun at anyone’s. Now I’m sure in time there’ll be times when that shouldn’t apply but for the moment that’s my take on it. If you don’t think anyone’s misfortune should ever be mocked then this probably isn’t the place for you or you may want to use the ignore function. As I said already though, if any post is particularly offensive to anyone for private reasons let me know.

Let’s keep the rugby thread and the pray thread joke-free.

Be kind.

This post made me sad this morning. Sadly and greatly missed by all us weirdos. @Lazarus too although I trust still going somewhere offline the aul hoore.

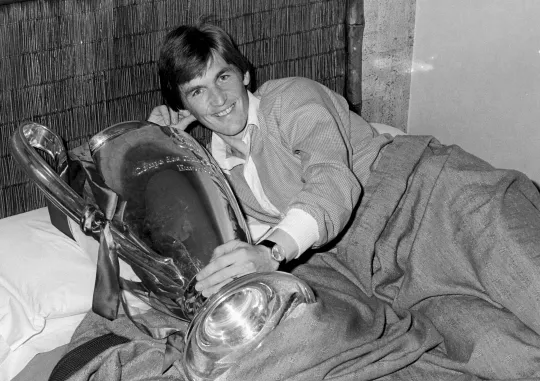

Kenny Dalglish on Hillsborough stress that made him quit Liverpool

Anfield legend on quitting Liverpool in the wake of 1989 tragedy, his unique player-manager role and acclaimed film-maker Asif Kapadia’s new biopic about him

Jonathan Northcroft

Saturday October 25 2025, 8.00am BST, The Sunday Times

Kenny Dalglish begins with young Kenny, comic-strip Kenny, the boy with the golden feet and golden smile who sprung from a Glasgow tower block to play football better than nearly anyone ever has on these isles. Kenny, the spearhead and brain of great teams. The scorer, the superhero. Kenny from heaven.

It ends with him mid-life, light gone from his eyes as he stares downwards, away from the cameras, at the February 1991 press conference where he shocked sport by resigning as Liverpool manager.

Bearing on him was the weight of Hillsborough and its aftermath — conveyed in one short, silent frame: a close-up of a tear on the older Kenny Dalglish’s cheek. “It’s always emotive,” he says of reliving events through Asif Kapadia’s beautifully judged biopic. “So get the tissues, for the end of it.”

Get the tissues. It’s typical Dalglish. Dry, deflecting, self-deprecating. And as we speak, on a grey afternoon in London, the least surprising thing is finding, at 74, this distinctive character hasn’t changed. Beside him, on the polished surface of a hotel’s tasteful coffee table is a can of Irn-Bru and a Dairy Milk bar — his normal “rider” from the production company throughout the process of shooting and publicising the film.

He was 38 and Liverpool’s player-manager when the Hillsborough disaster occurred at an FA Cup semi-final with Nottingham Forest in April 1989, causing the deaths of 97 fans. In the aftermath he and his wife, Marina, attended funeral upon funeral, visited the injured in hospital and became a rallying point in the long campaign for justice for those unlawfully killed.

He put his own strain and trauma second and his decision to quit, 22 months after Hillsborough, followed an accumulation of stress. “Everything was just piling up,” he admits, “and I wasn’t paying the club respect by trying to con my way through.”

He quit after a 4-4 FA Cup draw with Everton during which he “bottled” a tactical change, feeling too paralysed to make a decision. Leaning against the Goodison Park dugout, “I went to myself right away, ‘That’s you, you’re finished.’ ”

How long had things been “piling up”?’ “Oh, I don’t know, but about three weeks later I’d have gone back. Maybe it was a rest or a break away that you were needing, but you don’t get sabbaticals in football.”

Still, looking back through the lens of today’s world, with its greater awareness of mental health, the ending to Dalglish’s first stint as Liverpool manager (he would return in 2011) feels all the more poignant. The modern approach might have been to allow him a time out before returning to work — and counselling. Does he regret not having that?

“No. I think the decision I made was the correct one for the football club, my family and the fans, because that’s the people I was letting down.”

Did stress affect his sleep? “Och, I can’t remember. It would have, it must have. But nothing drastic.”

He regretted quitting for years but, in the film, Marina talks about him being “so, so stressed” and he admits there was a toll on their home life. Yet his perspective has remained unchanged throughout 36 years: any personal difficulties pale beside what the Hillsborough families have been through.

“It’s a small price I had to pay, we had to pay.”

From Stein’s Celtic to Di Stéfano comparisons

Kenny Dalglish retraces his journey through archive footage with Kenny narrating and the voices of others — principally Marina — chipping in. Previously unseen film footage, originally owned by Celtic, shows what a sensation he was: signed after impressing Jock Stein in an under-15s game and invited, at 17, to join a Celtic squad that had just won the European Cup.

These players, “The Lisbon Lions”, were among the best in the world. “But they never knew it,” he says. “They remained humble.” And Stein was paternal, “but you had no doubt in your mind who the manager was”.

Dalglish craved what he witnessed the Lions enjoy — the European trophy, the bus tour through a city’s giddy streets — but, after near-misses, concluded this wouldn’t happen for him at Celtic and he should try an English club. Yet he shelved such ideas for two years after Stein suffered a near-fatal car crash. “It’s just the way I was brought up. If somebody does you more good than harm, you want to repay them,” he says with a shrug.

Give loyalty, get loyalty: Dalglish’s values were those of Glasgow’s tight working-class communities. Stein reciprocated. When Dalglish eventually did ask for a transfer, Stein said: “I know someone who might be interested.”

“Boss, you’ve done everything for me,” Dalglish replied gratefully.

“All the best,” Stein drawled. “You wee bastard.”

The “someone”, of course, was Liverpool and Dalglish’s £440,000 British-record transfer was agreed “within five minutes” among him, Stein, Bob Paisley and the Liverpool chairman, John Smith, after a game at Celtic Park. Stein even drove Dalglish to Moffat, to be picked up by a Liverpool car and sped to Anfield for his medical.

Liverpool had just won their first European Cup and needed a new talisman, after the seemingly irreplaceable Kevin Keegan moved to Hamburg. “I wasn’t asked to replace Kevin Keegan,” he says. “I was just asked to sign. [Liverpool] never mentioned Kevin. Not once.

Liverpool player-manager Kenny Dalglish celebrates after scoring the winning goal against Chelsea, securing the 1985/86 Division One Championship.

“I couldn’t emulate Kevin. I had to be my own man. You’ve got a better chance of a wee bit of success if you are yourself.”

“Wee bit” is a very Kenny way of describing winning 19 major trophies as a player and manager for Liverpool, scoring 179 goals, setting up another 186, and having an Anfield stand named in his honour. Yet how could he not be down to earth? His father, Bill, a diesel engine fitter who loved his football, took the young Kenny to watch Rangers and was “eh …disciplined. He used to watch me play in the morning for the school team, then in the afternoon for [boys’ team] Possil YM. And if I did something wrong, he would nicely tell me about it.

“He was not so keen on telling me if I did something right. So that must have meant he was OK.”

When he fell for Marina the attraction included her similar background, the same family-orientated way of thinking. She was a pretty teenager who was helping out at the Beechwood pub, frequented by the Celtic squad, and owned by her father, Pat. Kenny took three years to ask her out and she wondered what kind of fancy car Scotland’s best young footballer might drive — but he turned up for their first date on foot and they caught the bus into town for a film and fish and chips.

They’ve been married 51 years and she, their son, Paul (who also became a footballer), oldest daughter, Kelly (Cates — the broadcaster), and younger daughters, Lauren and Lynsey, are his world. In the film he quips that Marina is “the best five pound I ever spent — on the marriage certificate” so what would she say about him? “That she was underpriced.”

There’s footage, on the plane home from beating Everton in the 1986 FA Cup final, of Kenny attempting a TV interview and Marina pouring a little bottle of champagne on his head. A lovely moment. “Oh, do you think so?” I suggest not many people would get away with doing that to him. “Aye, but there’s not many people like Marina.”

The film reminds you what an incredible footballer he was. Left foot, right foot, goals from everywhere, passes others could neither execute nor see. Telepathic relationships with team-mates like Graeme Souness and Ian Rush. Perhaps being British football’s first ever “false nine”. His famous way of getting on the ball, jutting out his bum and holding giant defenders at bay.

A theme is his football brain. During games he studied opposing goalkeepers, mind whirring, and scored the winner in the 1978 European Cup final with a chip after noting that the Bruges goalkeeper tended to dive low and early. He describes anticipating defenders’ positioning by looking at their shadows. There’s a clip of George Best describing Dalglish and Alfredo Di Stéfano as the greatest players he’s seen. “[Dalglish] is three or four moves ahead of everyone else,” Best says.

Yet, unlike Keegan, Dalglish never won the Ballon d’Or. A regret? “No, no, no. The individual trophies are nice, but they don’t count really.

“Some people say I maybe should have done more. Should have or could have, I don’t know, I don’t care. I don’t think I’ve done too badly.

“I don’t think [football] is about an individual. It’s a collective thing. You may get credit because you scored a couple of goals but there are others who don’t get credit for stopping goals. If everybody on the pitch does their job the best they can … that’s what I was trying to do.”

He was only 33 and with the family at Christmas when Liverpool’s chief executive, Peter Robinson, called to ask him to take over as manager when Joe Fagan retired at the end of the 1984-85 season. “I was under contract as a player with three years left. I thought I was playing OK,” he deadpans.

“[Being manager] hadn’t entered my head. It was an absolute shock. I spoke to my dad and I spoke to Pat, Marina’s dad. They both said the same thing: ‘If they think you’re capable, have a go.’ ”

He credits Paisley’s role in mentoring him, yet his own abilities as a manager should never be underestimated. It feels, today, that they are — even though Dalglish won more English titles as a boss than Arsène Wenger and Bill Shankly, and as many as Herbert Chapman.

The first featured the return of comic-book Kenny when, having left himself out of the team, injuries forced him to play and his introduction sparked a run of ten wins and one draw in Liverpool’s last 11 games, as they overhauled rivals in the title race. He scored the title-clinching goal at Stamford Bridge.

It’s unlikely a player-manager will ever win a major European league again. “The hardest thing was trying to pick the team. You’ve just been part of the dressing room and to come out of that and pick the team knowing you’re upsetting somebody was horrible,” he says.

Was it ever as enjoyable as simply playing? “Naw.” Not even when, after Rush moved to Juventus, he used the funds to sign John Barnes, Peter Beardsley, Ray Houghton and John Aldridge and create the incredible 1987-88 team? Watching them must have been a thrill. “Yeah, but it’s an even bigger thrill if you’re playing. But I don’t think Peter [Beardsley] would have let me in.”

The film cuts from that team’s finest hour and a half, an immortal 5-0 demolition of Forest on April 13, 1988, to facing them again one year and two days later. At Hillsborough. Kelly and Paul were at the game, Paul walking across the Leppings Lane end, where the fatal crush occurred, to get to his seat in the stand. For half an hour, while bodies were being borne away on stretchers that fans improvised from advertising boards, Dalglish didn’t know if Paul was safe. The fear, incomprehension and horror of what is unfolding is writ on his face, surrounded by fans, police officers and players looking to him to lead.

“It is emotional [to relive Hillsborough],” he says, “but more importantly it’s emotional for the families who suffered there. Unfortunately, we had to deal with a thing that should never have happened. But when we were struggling, which was often, they [supporters] were the ones that supported us. So it was our turn to be the supporters.

“The squad of players, the management, everybody at the club was fantastic, but it hit a lot of people badly and everybody had a different pace of moving on.”

The FA, under the chief executive Graham Kelly, was quick to decide the FA Cup should be played to a conclusion. The governing body asked Liverpool to fulfil their abandoned semi-final fixture at a time when funerals were still taking place and injured supporters were lying critically ill. That still rankles. “We were threatened with getting thrown out of the competition if we didn’t play the game,” Dalglish recalls.

“The football club did everything we possibly could to help the families, help them stand up. Unfortunately the same ethos wasn’t coming from the people who run the place.

“The people who made that decision aren’t at the FA any more so any criticism isn’t aimed at current members, it’s aimed at the people responsible for the decisions at Hillsborough. And it was embarrassing. I think. It was embarrassing.”

He’ll never forget Celtic’s gesture. On April 30, with Liverpool due to return to action against Everton, but players still not sure if they could face playing, Celtic hosted them in a friendly at Celtic Park — despite having played a tough game away to Aberdeen the previous day. Dalglish played, scored and smiled for perhaps the first time in two weeks. “It was a really important part of our rehabilitation. To play the game, 60,000 — I’ve never heard You’ll Never Walk Alone sung like that in my life. It was unreal.”

He reveals another gesture of football friendship, not spoken about previously, when — on the Monday morning after Hillsborough (a Saturday) — Anfield was opened for people to pay respects and lay flowers. “Fergie [Sir Alex Ferguson] and some of his people were the first there,” he says. “There’s a big rivalry between Liverpool and Manchester United, but the football world came together.

“Teams came from all over Britain. Evertonians who had never been to the ground came to show their respects.”

He took Kelly, then 13, and Paul, 12, to Anfield on the Friday. “They were hugely upset, so was I. And then we walked along the Kop and it was surreal.

“Messages left there at certain crush barriers. An orange placed there, because the old boy must have obviously brought an orange, or a bit of fruit for every game … and [Kelly and Paul] are going through this. And I’m going through it myself and thinking, ‘Have I done the right thing here?’ But we had to dae it. It doesn’t matter if it’s emotional or whatever.”

Narrating the film, his voice breaks as he describes how Paul and Kelly brought two teddy bears from their bedroom and tied them to the goalposts. “They wanted to go because they wanted to do something, and they wanted to tie the teddies to the crossbar. It would have been emotive, right? But I don’t think it did them any harm.”

Was he proud of how they conducted themselves? “Pffff. I was proud they even wanted to come. But, I mean, we’re only on the fringe of it. The real ones that suffered were the families. The relations, the people that died.

“We were ones that maybe got publicity. But it wasn’t for publicity. It was because it was the right thing to do.”

He doesn’t look 74. His sense of mischief has certainly never grown old. We chat about Fergie. For years the world misunderstood their rivalry — sure, it had its flashpoints when they managed opposing sides, but these were never more than squabbles between two Glaswegians with similar backgrounds who have known each other since adolescence.

These days they exchange messages regularly and their friendship was glimpsed at Anfield last Sunday when Ferguson was filmed offering Dalglish a chocolate button. “He stole them!” Dalglish says. “We get them [in the directors’ box]. He’s, ‘Anybody want these buttons?’ and I said no, no, and then, ‘Wait a minute, where’s my buttons?’

“And he’s standing there with the bag.”

Now he can see it all, from distance. Did what he went through change him? After winning the title with Blackburn Rovers he still had successes in the dugout, notably leading Liverpool to the League Cup in 2012, the club’s first trophy in six years. But he never produced another team with the joy of his 1988 side, and often seemed wearied by the media element of management.

“Everybody changes through time, don’t they? Whether you can go to one specific area and you say, ‘Well, that changed me for this …’ ” he says.

How long did it take him to return to normal after he stepped away from Liverpool, for the first time? “Oh, I don’t think I’m ever normal.”

He’s rightly proud of the film and was honoured that Kapadia — a Liverpool fan, whose masterpieces include Senna, Diego Maradona and Amy — wanted to tell his story. “It’s emotive talking about it. And the most important thing is there’s things that mean a lot to you, right?

“But the thing that means the most to me is you try your best, you might not be good enough but you do it honestly, you do it respectfully, and if it doesn’t work out, then fine. Look in the mirror and you’ll find the answer why.

“So that’s all I’ve done. I can go to my bed on the decisions I made and I can sleep. I can’t go to my bed thinking about what happened and what caused the reasons for it.”

• Kenny Dalglish will be shown in UK and Ireland cinemas on October 29 and 30 only. Watch on Amazon Prime Video in the UK and Ireland from November 4.